- About Us

- Columns

- Letters

- Cartoons

- The Udder Limits

- Archives

- Ezy Reading Archive

- 2024 Cud Archives

- 2023 Cud Archives

- 2022 Cud Archives

- 2021 Cud Archives

- 2020 Cud Archives

- 2015-2019

- 2010-2014

- 2004-2009

|

January 2010 - Greek & Aboriginal Australian Culture In Contact: |

Across Cultural Boundaries In Prose, Poetry & Beyond

Introduction

Scope

Since the 1970s, Greek scholarship in Australia has been steadily attracted to a cross-cultural journey, that is, to a comparative analysis of the intellectual tradition and creation of Australian Hellenism with that of mainstream Australia.

In this article, however, the cross-cultural journey will take the opposite direction, that is whether and how Australian Hellenism has been impacted upon by the culture of another Australian minority, that of Aboriginal Australians.

Demographics

According to the most recent census (2006) the self-identified indigenous peoples of Australia numbered 455,028 persons (409,525 Aborigines, 27,302 Torres Strait Islanders and 18,201 identified as both), comprising 2.3% of th e total Australian population of 21,522,662 and speaking about 145 indigenous languages, many of which are dialects (almost 110 of them critically endangered) out of the estimated original number of about 250 known indigenous languages and dialects which were spoken throughout Australia.

e total Australian population of 21,522,662 and speaking about 145 indigenous languages, many of which are dialects (almost 110 of them critically endangered) out of the estimated original number of about 250 known indigenous languages and dialects which were spoken throughout Australia.

It should be noted that indigenous Australians acquired the right to vote (abolition of Section 25 of the Constitution) and were included in the national censuses (abolition of Section 51 (26)) as late as the end of 1967 (1967 Referendum), while in 1992, the High Court abolished the concept of Terra Nullius (Mabo Decision), opening the way for the recognition of native title land rights.

In comparison, on the basis of the same census (2006) the self-reported persons of Greek origin consist of 365,200 (1.8% of the total population). In reality, however, their number may reach around 400,000, when considering those of Greek ancestry born in areas other than Greece (Cyprus, Turkey, Egypt, South Africa, and elsewhere), who may have identified themselves on the basis of their country of birth, a fact which also means that claims of 600,000, 700,00 or even more are unsubstantiated exaggerations. Of all these Greeks, 47% live in Melbourne and 29% in Sydney. Despite the dramatic increase in Greek emigration to Australia after World War II, especially after the 1952 agreement between the two governments, with a total of almost 250,000 Greek arrivals between 1947 and 1982, the 2006 census revealed that the number of Greek-speaking individuals has decreased from 269,775 in 1996 to 263,075 in 2001 to 252,222 in 2006. Yet Greek has remained the second most popular language other than English spoken at home in Australia – 1.3% of the entire population after Italian (1.6%).

Finally, although Greek emigration has declined since the 1990s to about 100, or even fewer, persons annually and many have repatriated, today the Greeks still constitute the fourth largest ethnic group of non-English speaking origin after the Italians (852,417), the Germans (811,541) and the Chinese (669,896).

The impact of Aboriginal Australian life and culture upon Australian Hellenism

Regarding the impact of the culture and life of Aboriginal Australians upon Australian Hellenism, and in particular upon first generation Greek immigrant artists (the scope of this paper), we are impressed by the broad spectrum of their inspiration in prose, poetry, theatre, music, painting and sculpture.

Literary expression (prose and poetry)

According to the preliminary results of my research, the earliest such writer appears to be the prose writer Alekos Doukas, younger brother of the well-known writer in Greece, Stratis Doukas. He emigrated to Melbourne in November 1927.

Doukas in his Greek-language semi-autobiographical narrative Under Foreign Skies, written in 1953-1958 and published posthumously (1963), presents his personal view of the situation of the indigenous people of Australia. He points out that the Aborigines were persecuted by the colonial British authorities of the time, deprived of their traditional lifestyle, displaced from their native lands, and even exterminated (p. 13, 61, 90, 136). He portrays them likably as simple and unpretentious people of the bush (p. 122), known for certain abilities and qualities, such as the prediction of periodical droughts (p. 122) and even being “more ethical and fair than us the Whites”, although applied “with primitive toughness” (p. 90). However, he also believed that their cultural development “stopped at the stage of the wandering ‘human hunter’ without even rudimentary settlement” (p. 12).

Doukas reflected the ideas of Social Darwinism of the 19th century. In accordance with these ideas, the Aborigines make their appearance in Doukas’ Under Foreign Skies not as developed full-fledged characters, such as his white co-workers and bosses – Australians, Jews and people from different countries of Europe. They pass through the pages of the book like shadows in the forest where the Aborigines lived and hunted.

As a true internationalist, though, Doukas expresses his opposition to the “White Australia” policy (p. 84), which consolidated understanding of “race” in terms of a dichotomy of white and non-white people across the world putting him ahead of his times.

Doukas’ case is very interesting on this particular cross-cultural subject as he appears to be the earliest Greek literary voice in Australia to reflect Aboriginal life and culture in his writing, almost half a century after the onset of the 20th century of this body of literature in Australia. Undoubtedly this arose from his early attraction to “Australian history, particularly that of the Australian Aborigine and the Australian working people” (Stefanou, 1983: 16), as well as his personal experiences as a seasonal fruit picker and vine pruner in rural areas in Victoria and New South Wales. It is true that the Greek writers of his generation and before him had been almost exclusively occupied with hellenocentric subjects (love for Greece, etc.), and subjects relating to the harsh conditions of immigrant life (nostalgia for the native land and the loved ones left behind, the Odysseic dream of final return to the homeland, etc.).

Doukas stands out as an advocate for the abolition of the “White Australia” policy and for recognition of Aborigines as a relevant part of Australian society.

At the same time in Western Australia another significant poet, short story writer and playwright, Vasso Kalamaras, was making her appearance. Kalamaras emigrated in 1951 settling in the rural town of Manjimup, 300 kilometres south of Perth, where she worked on her father-in-law’s tobacco farm and came into contact with the indigenous people of the area, an experience which would later be reflected in both her Greek and English-language literary writing. One such evidence is her poem “Corroboree” (an Aboriginal assembly of sacred, festive or warlike character) included in her bilingual collection Landscape and Soul: Greek-

Australian Poems.

In this poem Kalamaras reveals the magnitude of the Aboriginal tragedy:

[…]

We were there,

more pitiful than the state you have been reduced to,

as we listened to

every despairing voice

that told of your gods

who were dying with you, inside you.

Passing like thunder through that great long horn,

the didgeridoo,

there was doom in every note

it cried out

a human voice.

Your people are lost.

(Landscape and Soul, Perth, 1980: 47 in Kanarakis, 19912: 177)

Kalamaras is not a simple spectator but a most sympathetic participant in this collective human drama. The Aborigines’ social problems and mistreatment resulted in a radical decline of their population from an estimated pre-1788 population of 750,000 to approximately 93,000 by 1900 and the loss of many of their languages and traditions. This is the concept which Kalamaras effectively conveyed in the last line of her poem when she exclaims to all Aborigines – “Your people are lost”.

A close examination of the poetry and prose of first generation Greek immigrant writers reveals the creation of a number of interesting and highly sensitive pieces by some of our writers whose knowledge derives either from personal study of Aboriginal society and lifestyle (indirect influence) or from first hand experiences and interpersonal communication with the indigenous people themselves (direct influ ence), as with Doukas and Kalamaras.

ence), as with Doukas and Kalamaras.

Some representative cases of the latter category of writers are the poet Adrianos Kazas, the poet and short story writer Kostas Rorris and the bilingual poet and playwright Yota Krili – all of Sydney, as well as the Melbourne poets Dimitris Tsaloumas and Nikos Ninolakis.

These writers were affected by the impact of the conditions of life, the local environments, Aboriginal spirituality and folklore, and the individuals they encountered, transforming their memorable experiences into literary pieces. Each of these writers transformed their memorable experiences into significant literary pieces distinguished by powerful images of Aboriginal life and pristine landscape.

Some of them went on the road and into bush or outback to see “Aboriginal Australia” firsthand or were invited visitors. Rorris, for example, was invited by an Aboriginal who worked in his café in western Queensland to visit her extended family living in the bush. Others travelled as tourists, like Kazas, to popular places such as Coober Pedy and Uluru [Ayers Rock] and Alice Springs, whereas Ninolakis, Tsaloumas and Krili have all been enquiring travellers. Krili, for example, driven by her life-long commitment to social justice issues, went backpacking for three months in 1999 in South Australia, Western Australia and the Northern Territory, and can be seen as a social explorer.

Thematically this cross-cultural impact appears broad and impressive. Some of these themes are:

1. The gradual erosion of traditional Aboriginal lifestyle since colonial times due to the new social order imposed by European society and to the separation of children from their families by forced removal (New South Wales from 1883 to 1969), prohibition of the use of their own languages and performing their own rituals etc.

In her poem “Dead Finish” Yota Krili delineates with sensitivity:

Their dark presence

always conspicuous

in the fringes of towns.

They carry no spears, no coolamons

only plastic bags from the supermarkets.

Depression, a bird of prey

picking at the marrowbone.

[…]

2. The exploitation and destruction of the local Aboriginal ecosystem by companies mining for uranium and gold, logging, etc., forcing them out of their ancient and familiar environments to become people of the social periphery.

In his poem “The Green Ants” Dimitris Tsaloumas points the finger at the unethical exploiters of uranium mining in Aboriginal land with impressive irony:

Down in the Antipodes

[…]

in distant Arnhem Land

where time still sleeps

and wizened men

with rusty skins

moan their dirges

[…]

there the enlightened ones

went to search and found

the mineral of salvation

Uranus’ gift

wealth

to clothe the vanquished race

and reward the labours of the just.

[…]

Ants or no ants, let the mining

and the exporting begin at once.

[…]

(Observations of a Hypochondriac, 1975: 60-63 in Kanarakis, 19912: 2, 286-289)

3. The occupation and desecration of their sacred places (Uluru etc.) which were often transformed into tourist sites due to the lack of understanding and appreciation of Aboriginal culture and the deep and vital physical and spiritual interconnectedness between the Aborigines and their environment.

Krili reflects on the sad fate of one such sacred site – the internationally recognised Uluru, the largest monolith on the planet, in her poem “Rosie” (Triptych: 24-25).

[…]

O Rosie

where is your home?

Where have you been?

I expected you to collect

the entry fee to Uluru-Kata Tjuta

but the hand that took the money was white.

[…]

4. Finally, the moments of understanding and appreciation of Aboriginal culture and spirituality as well as feelings of regret. These writers come to the point of realisation that Aboriginal culture is not inferior, but different, replete with ancient myths, traditions and beliefs, and that the Indigenous people in general have knowledge and understanding of their environment and thus an almost religious affinity with it. Language, culture and identity are intrinsically linked.

4. Finally, the moments of understanding and appreciation of Aboriginal culture and spirituality as well as feelings of regret. These writers come to the point of realisation that Aboriginal culture is not inferior, but different, replete with ancient myths, traditions and beliefs, and that the Indigenous people in general have knowledge and understanding of their environment and thus an almost religious affinity with it. Language, culture and identity are intrinsically linked.

Relevant examples of this “awakening” and sense of regret are found in the poem written in 1969 by Nikos Ninolakis “Further on from Moulamein…”.

Ninolakis relates the personal spiritual awakening which he experienced as he made his way, guided by an Aboriginal spirit, through the depths of a powerful and overwhelming thick forest, like a sacred temple, around Moulamein, a rural town in southern New South Wales, which he visited in 1969. The spirit revealed to him that this forest had been inhabited from immemorable times by Aborigines, now vanished after their defeat by Whites.

[…]

Over in that wilderness

Further on from Moulamein

Where the wasteland ended

Rose like a castle wall

The silent bushland

[…]

I entered naked like a soul

Beneath the heavy shadows

[…]

“The bushland is ill-fated”,

The spirit told me whispering

[…]

“But there came the tempest

And the bark of the tree

Was too feeble and young

To make a stand

Against iron and fire.”

[…]

In a similar vein, Kostas Rorris describes in a short story entitled “As long As there Are People…” his personal spiritual experience in the western Queensland bush when an Aboriginal elder surprised him with his wisdom deriving from his people’s ancient knowledge of their culture and environment. Rorris had approached the elder in his “fervent socialist” manner ready to indoctrinate the old man, only to realise at the end of their discussion that the Aborigines practice their own form of socialism, without the weaknesses evident in the socialism of the White society.

5. Another common point shared by the first generation Greek writers, and by the writers included in this paper, is that their understanding and appreciation of Aboriginal culture is clearer more in recent decades than any other time in the past, particularly of Aboriginal art (literature, painting, music etc.) and its exponents. An eloquent example of this are two poems, one entitled “To Albert Namatjira”, the noted Aboriginal painter, by Stathis Raftopoulos, first published in Greek in 1963 in the Melbourne newspaper Sfika (Wasp), and the other poem, entitled “A Drawing in the Vastness of the Eucalyptuses”, written by the poet Nikos Nomikos, which he dedicated to Kath Walker (Oodgeroo Noonuccal ) (1920-1993), the Aboriginal poet, activist and public speaker on Indigenous rights.

Raftopoulos’ poem of six rhyming stanzas refers to Namatjira’s life and work (today his paintings are held in prominent collections in and out of Australia), the poverty and contempt he endured, his temporary imprisonment, but also his faithful maintenance of Aboriginal customs and traditions to the end, while Nomikos’ poem in free verse artfully acknowledges Kath Walker’s articulation of the feelings of Aboriginal people for the rest of Australia and also her passion for peace and a just world.

Aspects of Aboriginal culture have left their mark not only on the adult literature of Australian Hellenism but even on children’s literature, though comparatively quite recently.

A representative example is the Sydney poet and prose writer Beth Georgellis whose general work focuses on Greek children’s literature. In her prose work Zeus the Koala and the Magic Egg, published in 1999 in separate Greek and English versions, blends with affection and sensitivity most appropriately for children, themes such as the Ancient Greek origin of the Olympic Games and references to Aboriginal culture – the sacred site of Uluru, the wise Aboriginal elder, Aboriginal paintings on the walls and floor of his cave, the harmony of the Aboriginal elder, and therefore of Aborigines in general with the animals of the Australian bush, etc., promoting peace and harmony.

Theatre

Although the Aboriginal impact on the literature of the Greek Australians is quite rich, it is very slim and recent on the Greek immigrant theatre logos and praxis.

The most recent and apparently only example in Greek adult theatre in this country is Sophia Ralli-Catharios’ play Crossroads staged in 1991 in English and in 2008 in Greek at the Canberra National Multicultural Festival by the (Hellenic) Art Theatre and repeated the same year at the Greek Festival of Sydney. Apart from the issues of gender, race and ethnicity, and cultural and social differences, the playwright explores the spirituality of two cultures of ancient origins: the Greek and the Aboriginal, breaking down ethnic distinctions and advocating the oneness of the human race. The playwright also sets the appropriate mood by incorporating an Aboriginal performer playing the didgeridoo at certain key points of the production.

Apart from adult theatre there is also a similar contribution in children’s theatre. Until now the main exponent has been Vasso Kalamaras. In this area she has written two bilingual (Greek and English) children’s plays, Little Eros (for little children) and Olympus on the Porongorups, both produced in English in Perth in 1982. The first play refers to a celebration involving the little Greek god Eros and Aboriginal children, animals and trees, teaching friendship and brotherly love within the Australian landscape. The second play captures the atmosphere of a symposium of the Greek gods on the Aboriginal mountain Porongorups. The play brings together the two ancient religions and their mystical wisdom within the natural environment, as well as the theme of the human need to survive.

Music

Although Aboriginal music, in its artistic combination of vocal and instrumental sounds into melody, harmony, and rhythm, differs from the Greek, a cross-cultural encounter has been achievable and welcoming, although it did not occur until as late as the last decades of the 20th century.

The most well-known example has been the inspiring Melbournian singer, guitarist and songwriter, Costas Tsicaderis. Tsicaderis and his Ensemble formed in 1982, and in addition to many other musical activities over the years, gave a recital on 6 October 1985 at the Boite of the Universal Theatre in Melbourne with a special guest, an Aboriginal musician playing the didgeridoo for a composition based on Nikos Ninolakis’ poem “Beyond Mulamein”.

The text accompanying a tribute CD of his original compositions entitled “The Mighty and the Humble” states that in “Beyond Mulamein” “Costas fuses the traditional instruments of bouzouki, didgeridoo and flute to represent the voices of the Aborigine (didgeridoo, an instrument producing sounds which “spring out of their natural environment and their land”), the white settler (flute) and the immigrant (bouzouki)”.

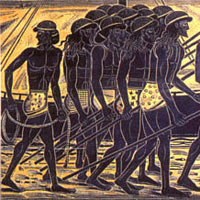

Painting

The first generation immigrant painters of Greek origin have not fallen behind on this cross-cultural thematic aspect of visual art, although, comparatively with the rest of the first generation Greek painters they belong to the minority, like those in the fields of literature and the theatre.

As far as it can be ascertained, the earliest, and also the first full time professional Greek painter in Australia was the Castelorizian Vlassis Zanalis (1902-1973) or Vlase Zanalis as he was more widely known.

Zanalis became an impressively productive artist whose work is diverse in stylistic features and content spanning almost half a century. Although by the end of the decade of the 1930s he had become quite renowned as a portrait painter (self-portraits as well), his range of work also extended to religious painting, especially Byzantine art linking him with both the Orthodox tradition and his Greek cultural heritage, and to Australian themes (suburban and outback landscapes, aspects of industrial and mining life and Aborigines and Aboriginal subjects).

With a keen interest in the Australian landscape and in Aboriginal culture and life, invigorated by personal study as well, he sought inspiration from direct contact with Aborigines in their tribal setting, as well as the outback landscape. In the decades after World War II (from late 1948 until 1968) he set out on several extended outback journeys, living sometimes for months with northern Aboriginal tribes of Western Australia (the Dadaway on the Forrest River Mission which he visited three times, who also initiated him into their tribe giving him the names Unjulmara and Kalaroogari, the first for everyday social use and the second for use in official ceremonies, and also other tribes in the Kimberleys). These stays enabled him to portray Aboriginal people, their sacred sites and ceremonies but also black madonnas, making him the first white painter to work among them at a time when white people, other than missionaries and government officials, rarely even visited them.

From 1968 until his death in Perth, together with other subjects, he continued painting Aboriginal figures and ceremonies (88 in all), but from memory, which he intended to be his memorial to the Aboriginal people, in his own words “the fine people of a proud race”.

Another first generation Greek immigrant visual artist whose work reveals direct Aboriginal influence is the contemporary painter Nikos Soulakis. Like Zanalis, Soulakis has been inspired by his direct personal contact with Aboriginal culture and life, but they differ in that Zanalis’ work derives from his experience of Aborigines in their natural physical environment, whereas Soulakis’ paintings are the result of his contact and observation of urbanised Aborigines in Melbourne.

Having emigrated to this city in 1966 and settled in the working class suburb of Fitzroy highly populated by immigrants and Aborigines, he was touched by the latter group’s low socioeconomic living conditions and, comparing them with his own early immigrant situation (and of other first generation immigrants as well), he empathised with them even more because in his eyes they appeared to be deprived immigrants in their own ancestral land.

Another characteristic of Soulakis’ forty-five years of work in Australia, is that he has been quite productive with Aboriginal themes, especially their art, in combination with the uniquely harsh yet beautiful vast red and ochre expanse of the Australian landscape and the way it appears to a non-Aboriginal, that is Greek immigrant’s eyes.

Among the exhibitions which have featured his painting on Aboriginal themes, in 1991 he organised a personal exhibition at the Victorian Artists’ Society Galleries in Melbourne with a total of twenty-eight works, all on this cross-cultural, Aboriginal – Greek theme, and entitled “Between Two Cultures”. Through this exhibition, Soulakis blends the symbols and colours of the ancient Greek and Aboriginal cultures to present their cultural richness and to emphasise the need for friendly co-existence between all Australians and the Aboriginal.

Sculpture

Athanasios (Arthur) Kalamaras, described as West Australia’s finest figurative sculptor, is a member of the well-known family of artists and writers. Born in Greece and emigrating with his parents to Australia, he later followed in his father Leonidas’ steps, becoming a prominent contemporary sculptor as well as painter, deeply influenced by the Hellenistic tradition.

With reference to Aboriginal themes, in 1979 he completed his large stone relief (2 metres high x 16 metres long) “Minmarra – Gun Gun”, a place where the spirits of women rest. This memorial, incorporating Aboriginal symbols and beliefs, combines them with honouring the pioneer women of Western Australia. Commissioned by the Women’s Committee of the Sesquicentenary (150 years) celebrations, it is situated in King’s Park Botanical Gardens in Perth.

Conclusion

Based on the results of my ongoing research, it has been established that Aboriginal culture, art and history, which are widely accepted today as an integral part of the wider multicultural Australian national identity, have not left untouched (through direct and indirect contact) first generation Australian Hellenism, particularly in the arts. Of course, for them to reach this point in the 21st century, they have struggled for many years against social injustice and division, while striving for what might be called the three Rs: recognition, respect and reconciliation. This impact, noticeable especially since World War II, reveals how two ancient cultures and traditions have come into contact in this country, acknowledging their historical legacies and highlighting that they have survived and continue to grow in this land.

This paper has presented how some first generation immigrant heirs of the oldest culture of Europe have responded artistically to the oldest culture of this continent of Terra Australis, and in closing I acknowledge the debt we owe to these Greek writers and visual artists who have enhanced our awareness and appreciation of Aboriginal Australia – its people, culture and the issues which have been confronting them.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY

ABS, 2007 Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2006 Census of Population and Housing, Australia. [Canberra]. Catalogue No. 2068. 0-2006 Census Tables.

ABS, 2008a Australian Bureau of Statistics, Year Book Australia, 2008, (1301.0). [Canberra], 7 February [http://www.abs.gov.au].

Australian Human Rights Commission, 2008

Australian Human Rights Commission, Face the Facts. [http:www.humanrights.gov.au/racial_discrimination/face_facts/index.html].

Jupp, 2003

James Jupp, From White Australia to Woomera: The Story of Australian Immigration. Port Melbourne, Victoria: Cambridge University Press.

Kanarakis, 19912

George Kanarakis, Greek Voices in Australia: A Tradition of Prose, Poetry and Drama. Sydney: Australian National University Press.

Kanarakis, 1997

George Kanarakis, In the Wake of Odysseus: Portraits of Greek Settlers in Australia. Greek-Australian Studies Publications Series, 5. Melbourne: RMIT University.

Kanarakis, 2003

Γιώργος Καναράκης, Όψεις της λογοτεχνίας των Ελλήνων της Αυστραλίας και Νέας Ζηλανδίας. Series: Ο Ελληνισμός της διασποράς, 2. Athens: Εκδόσεις Γρηγόρη.

Lourandos, 1997

H. Lourandos, Continent of Hunter-Gatherers: New Perspectives in Australian Prehistory. Oakleigh,Victoria: Cambridge University Press.

Rose, 2001

D.B. Rose, “The Indigenous People”. In The Australian People: An Encyclopedia of the Nation, Its People and Their Origins, ed. J. Jupp: 4-9. Oakleigh, Victoria: Cambridge University Press.

Stefanou, 1983

Vassilis Stefanou, “The Struggle of Aleck Doukas”, Antipodes 11, 16: 15-16.

White, 1981

Richard White, Inventing Australia: Images and Identity 1688-1980. Sydney: George Allen and Unwin.